Rise in Mandatory Health Warnings on Consumer Products

Attempts to reduce the visual appeal of consumer products – for health reasons – have been most noticeable in the tobacco sector to date.

Some governments require graphic warnings on products and even ‘plain packaging’ – where trademarks must be removed or greatly limited; and colours and fonts standardised, so that the products are nearly indistinguishable.

A growing trend in the retail industry is the adoption of warning signs on packaging in the food and alcohol sectors. Disproportionate measures such as ‘plain packaging’ have not been implemented, but there is a rise strategies to reduce the visual appeal of certain products.

Chile‘s ‘Stop’ sign

One piece of legislation that has attracted the attention of World Trade Organisation (WTO) members in the Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) is an amendment to Chile’s Food Health Regulation.

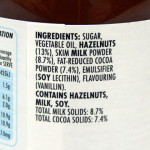

Decree No. 13 of April 16, 2015, requires a warning message in the shape of a black octagon (like a ‘Stop’ sign for traffic) to be placed on the front of the package with the words ‘high in…’ when food products exceed certain levels of energy, sodium, sugar or saturated fats.

Between 2013 and 2015, concerns were raised by several WTO members at meetings of the TBT Committee. This had mixed results.

Chile initially offered to decrease the scope of products affected by the measure; proposed the use of ‘Excess in …’; and altered the symbol to be used. But the final version of the amendment, effective June 27, 2016, will revert to ‘high in …’ and the black octagon.

The limits triggering the warning will also be made stricter over time:

- From June 27, 2016, solid food with 22.5gm/100gm of sugar (and liquid foods with 6gm/100gm) will have to be labelled with a black octagon, which states ‘high in sugar’.

- From June 27, 2017, the threshold will be lowered to 15gm/100gm of sugar (and liquid foods containing 5gm/100gm).

- From June 27, 2018, the label will be required for solid foods containing 10gm/100gm of sugar, but the liquid foods threshold will remain the same.

The limits for energy, sodium and saturated fats in solid and liquid foods will be similarly reduced over this period. At a meeting of the TBT Committee from Nov 4-6, 2015, Chile said it would review the impact of the measure in two years.

Proposals in Europe and the US

Use of the ‘traffic light’ warning label in parts of Europe is also of great concern to the food industry. This seeks to transmit naturally complex messages (the full nutritional profile) through a very simple means (a colour).

In June 2013, the UK issued a set of guidelines to be applied in cases where operators decide to use colour-coding as an additional form of expression. The ‘traffic light’ scheme includes affixing a label on the front of pre-packed foods and use of a colour-based code (red, amber or green) to draw attention to the amount of certain nutrients.

Fortunately, in October 2014, the European Commission formally opened proceedings against the UK for its ‘traffic light’ system due to concerns that it is more trade restrictive than necessary.

The French Parliament is considering a ‘simplified’ nutrition labelling scheme that takes into account the caloric, fat, saturated fat, sugar and salt content of food. It would combine the results on a five-point scale with dots coloured green, yellow, orange, pink or red. The scheme is included in the draft Public Health Act, which is under debate.

On Oct 27, 2015, members of the French Trade and Retailing Federation presented their proposal for a national simplified nutrition labelling scheme to various ministries and consumer associations, at a meeting organised by the Ministry of Health.

The proposal, called Aquellefréquence (‘how frequently’), specifies an algorithm for classifying food products by four colours (green, blue, amber and purple), depending on how often they should be consumed.

In the US, several initiatives have been established at the state- and city-level. Notably, San Francisco adopted legislation in June 2015 requiring advertisements for sugar-sweetened beverages to state a specific health warning.

Threat to food producers

For the most part, these anti-competitive industry practices are tolerated by governments, but the risk is that they may soon become, in differing forms and scopes, part of mandatory schemes imposed under specific regulations pursuing health protection objectives.

Producer countries must play an active role in monitoring policies and labelling schemes imposed by trading partners. This is to prevent decisions from being conceived and implemented in a manner that is disproportionate, distortive and discriminatory.

Any measure that demonises specific products or uses over-simplified slogans or labels to discourage consumption of certain substances should be resisted. The systemic interest at stake is too great to let these regulatory schemes develop unrestrained by the applicable WTO law.

Fratini Vergano

European Lawyers

Leave a Reply