The True Picture

MALAYSIAN farmers have over the last generation harnessed modern agricultural technology and techniques to increase their yields. This has been a blessing for consumers as it provides them with more food at lower prices. And it has also been a blessing for thousands of small farmers who are more productive, earning more income for themselves and their families.

But the successful adoption of high-yield agriculture has its critics, mostly among Western Environmental Non-Governmental Organisations (WENGOs). These groups claim that the conversion of forest land for agriculture is leading to alarming rates of deforestation. WWF and others have made it the primary cause of their global campaign against palm oil expansion.

These same groups claim that agriculture expansion is being driven by profit, or due to biofuel demands from wealthy countries. But in the case of palm oil, research points to increased demand as a result of a growing world population.

And with the droughts ravaging crops in the United States, increased demand for palm oil to compensate for reduced soya yields is inevitable.

But according to new research, the WENGOs are wrong.

A peer-reviewed article in the prestigious journal Science confirms the conclusion of forestry experts from US environmental consultancy Winrock International, that greenhouse gas emissions from deforestation are only 25% to 50% of previous estimates which have been used by other researchers to claim deforestation generates 20% of global emissions.

The initial findings, reported by Winrock in 2010, have been studiously ignored by WENGOs until now. Peer reviewers confirm the Winrock estimates that emissions from deforestation between 2000 and 2005 was just 10% and could be reduced further by 5%. As yet, the sequestration of carbon from regrowth of forests and replacement plantations has not been assessed.

This research was funded by the World Bank. A team of scientists used satellite imagery from the US space agency NASA to get a comprehensive understanding of what’s happening.

With these latest and more accurate figures, the contribution to global greenhouse emissions from Malaysia’s agricultural expansion can be seen in its proper context – it accounts for a tiny 0.025% of global emissions, or 1/100th of the share of aviation emissions.

These new findings demonstrate what those of us in the Malaysian palm oil industry have long suspected: that the economic benefits from sustainable land conversion for agriculture far outweigh any cost.

The findings undermine programmes such as the United Nations’ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+). This programme sought to establish an international market for carbon credits by paying developing world communities not to cut down their forests.

But this misguided programme was conceived before its architects had a thorough understanding of the realities of deforestation – and not for the first time. This follows similar scandals such as inflated claims of Amazonian deforestation and glacier melting in the Himalayas.

What the architects of programmes such as REDD+ missed is that the development taking place in Malaysia is similar to what has taken place in Japan, the United States, and Western Europe.

In these developed regions, farmers invested in sophisticated technology and engaged in domestic and international agriculture trade. This enabled these regions to feed growing populations and develop beneficial trade links.

Just as no one believes that Japan, the US or Europe should return to pre-modern agricultural methods, no one should argue that Malaysia would be wise to adopt more primitive forms of agriculture. Indeed, the adoption of modern agriculture enables countries to produce more food to satisfy growing demand utilising less land.

Malaysia is even setting a new and uniquely high international standard for agricultural modernisation by using less than 25% of land area for agriculture. At the recent Rio Summit, the nation’s political leaders pledged to retain 50% of the country’s total land area as forest. This far exceeds the 17% of forest land required to maintain conservation agreed to at the 2010 Nagoya Biodiversity Summit.

The new findings about deforestation and emissions come at an auspicious time. There is renewed global attention being paid to the need for greater food security. Delegates at the recent Rio+20 summit prioritised poverty mitigation and food security over environmental regulations.

Perhaps this is one benefit of the long and frustrating financial crisis. World leaders are once again forced to take stock of what’s truly important for the well being of their citizens and the rest of mankind.

Ensuring that the nearly 10 billion people who will share the planet by 2050 have enough food to live a decent life has to be a global priority. Malaysians should be proud that they are part of the solution to meet the global challenge of hunger.

Tan Sri Dr Yusof Basiron is CEO of the Malaysian Palm Oil Council.

This article was published in The Star newspaper on August 1st, 2012.

Time for the truth to come out.

Now the Tax had passed what is the Malaysian & Indonesian Govt going to do ? More RSPO ? I think it is high time the 80% of World producers meet and take joint measures to boycot French products It is the only weapon we have y do they want to increase the Duty by 300% ? They never think about the poor smallholders trying to sell their Palm fruits why should they ? I hope a formal complaint to WTO is what the Govt officials of both Malaysia & Indonesia be lodged before Christmas 2012

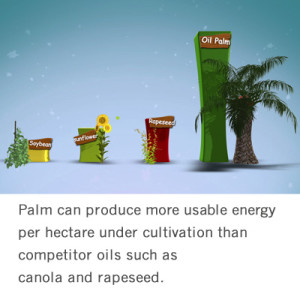

It may seem inevitable that large areas of Amazon forest will be converted for agriculture, but there are ways to mitigate the most serious environmental impacts of the transition. Developers can be encouraged to adopt cultivation methods promoted by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil — an industry-led initiative to improve its environmental performance. These include using natural pests and composting in place of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers whenever possible, implementing no burn policies, and creating catchment ponds to prevent palm oil mill effluent (POME) from entering waterways where it would damage aquatic habitats. Better enforcement of existing Brazilian environmental laws — including requirements to leave a portion of one’s land forested and riparian buffer zones — coupled with Brazil’s real-time satellite monitoring of forest cover could further reduce the worst impacts of extensive palm oil cultivation in the Amazon. Because oil palm plantations offer higher yields on a per hectare basis than either soy or beef production, the establishment of regulations that restrict new development to already cleared lands or secondary forests could result in a net economic gain for the region without the need to clear more forest. In a sense, if the highly productive oil palm plantations replace low-intensity cattle pasture already established in the region (without displacing ranchers or farmers into forest areas), the Amazon may well be richer economically and biologically. An important component to this would be the maintenance riparian zones and migration corridors along with the protection of critical habitats.