Analysis: French Draft Law on Biodiversity

On March 17, the French National Assembly (Lower House of Parliament) adopted a revised version of the Draft Law for the Recapture of Biodiversity, of Nature and Landscapes (Draft Law). It provides for yearly increases until 2020 to a special tax on palm oil, palm kernel oil and coconut oil – but makes an exception if these are certified as sustainable.

The Draft Law has been sent back to the French Senate (Upper House) for consideration. If adopted and then implemented, the tax will significantly hinder the importation and use of palm oil, as well as food products containing palm oil.

No dates have been set by the Commission on Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development for discussion of the revised Draft Law. Similarly, no date has been set for a second reading and subsequent vote by the Senate, but this will likely take place between May and June.

As matters stand, it appears that the special tax on palm oil will grow from the current EUR 103.71 per tonne, to EUR 133.71 per tonne in 2017 and all the way up to EUR 193.71 per tonne in 2020.

The special tax on palm kernel oil and coconut oil will grow from the current EUR 113.14 per tonne, to EUR 143.24 per tonne in 2017 and EUR 203.14 per tonne in 2020.

These levels must be compared to EUR 188.96 per tonne of olive oil, EUR 170.13 per tonne of peanut and corn oil, and EUR 87.16 per tonne of colza oil, among others.

Confusing health claim

Clearly, there is no uniformity of treatment of ‘like products’. There is also no scientific basis if (as proponents claim) the objective of the tax is to discourage consumption of saturated fats, which contribute to obesity and cardiovascular disease when consumed in high amounts.

The discrimination and lack of scientific basis are even more evident and disturbing if compared with the absence of a special tax on oils derived from cocoa butter, shea butter and animal fats. The food industry uses animal fats and milk, which often have a very high content of saturated fats.

If the French really want to fight obesity and cardiovascular disease – undoubtedly a legitimate policy objective – it is not clear why it does not neutrally tackle all ‘like products’ on the basis of their saturated fats content. Why does it discriminate on the basis of origin of the oils, among and between vegetable oils and animal fats?

Environmental argument unclear

Another stated objective is to fight environmental degradation and deforestation, and to encourage consumption of sustainable palm oil as well as its certification. However, it is not clear which sustainability criteria will apply to products derived from palm oil, in order to qualify for the proposed tax exemption.

No criteria are given, but the implementing mechanisms will likely be adopted at a later stage by decree. Even so, and while this objective may be noble in its intent, it appears discriminatory inasmuch as no similar environmental sustainability criteria apply to other oils, whether of vegetable or animal origin.

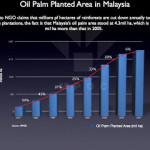

Forests are being cut down around the world to clear land for soybean production, cattle grazing and the production of other commodities used in the food industry. Similarly, many vegetable oils that are used are not sustainable in that their yield per hectare is greatly inferior to that of palm oil and require abundant herbicides, pesticides and fertilisers to be produced and applied.

Why is France focusing only on the environmental sustainability of palm oil? Why are there no scientific criteria on which to base its proposed measure?

From a logical if not legal perspective, the mixing of the nutritional and environmental objective into a single ‘special tax’ is, at best, singular. Assuming that most palm oil used for human consumption is sustainably produced, does that mean that its use would no longer be considered problematic from a nutritional perspective?

Both sustainable and unsustainable palm oil contain saturated fats. Yet, only the consumption of unsustainable palm oil would be discouraged for purposes of fighting obesity and reducing cardiovascular disease. This is yet another indication that the French measure is poorly drafted. The problem is not palm oil per se and it must not be targeted.

Swift engagement

All stakeholders must counter the proposed measure before it is adopted. In particular, bilateral discussions with the EU and France must be requested as soon as possible within the WTO framework.

For example, at the meeting of the WTO Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade in Geneva from March 9-10, 2016, Indonesia had raised a Specific Trade Concern on the proposed French measure vis-à-vis the EU.

There is a need for palm oil producing countries to engage with the French government, Senate and National Assembly, within all available avenues. They must impress upon legislators that this measure would be discriminatory, not scientifically based, not the least trade restrictive measure available, and a disguised restriction to international trade.

The first objective of any formal (i.e. diplomatic, political, commercial and technical) engagement with France should be to clearly understand the objectives of the measure; the details of the ‘special tax’; and the impact on palm oil vis-à-vis competing ‘like products’.

France must scientifically explain the environmental criteria for exemption from the special tax, together with the related certification mechanisms. It should also provide enough time for the affected WTO members to review the measure and convey their comments and alternative solutions. As it stands, France appears to be falling short of these requirements under WTO law.

FratiniVergano

European Lawyers

Leave a Reply