Good News From Rio

World leaders at Rio+20 endorsed a statement on fighting poverty and upholding food security.

THE recent multinational environmental summit held in Rio proved a remarkable victory for the developing world. There is now a greater degree of clarity when it comes to the global economic and social agenda. The interests and perspectives of the residents of emerging economies now carry significant new weight.

For example, issues of poverty alleviation and food security have moved squarely to the top of the global discussion. At the same time, many of the anti-growth ambitions of environmental NGOs were limited and firmly rebuffed.

While many industrialised economy representatives, particularly from Europe, initially pushed for new and onerous regulations on climate change and agricultural land use, their efforts largely proved unsuccessful.

In a unified voice, representatives from developing countries demanded that assembled delegates address economic and social needs in addition to environmental concerns. While the final official statement from the conference once again embraced sustainable development, it stated explicitly that robust economic growth and rising living standards must be part of any reasonable understanding of sustainability.

One way to see the success of Rio is to take stock of what was left unsaid in the summit’s final statement. For example, there was no reference to the United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation, and the Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD) programme. This programme has long received green group support as it seeks dramatic limits on plantation-scale agriculture. Developing world representatives have made it clear that programmes such as REDD will have a profoundly negative effect on small farmers and economic growth. REDD received significant pushback in Rio.

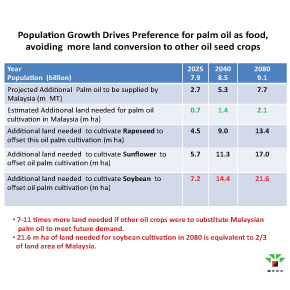

Indeed, the statement’s section on food security highlighted the importance of increasing agricultural production. Increasing yields will be needed if we are to feed a planet of 10 billion people by the year 2050. This view is supported by respected Western institutions like the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Many residents of developed nations have the luxury of forgetting just how important plantation-scale agriculture was to their economic rise. Today’s emerging markets, however, are keenly aware of the need for investment in the agriculture sector to power increases in jobs, incomes, and opportunities.

It’s also useful to note the genuinely good official scientific news that emerged during the same week as the Rio summit. A major report was published in the journal Science showing once again that previous estimates of greenhouse gas emissions from forestry and land clearing – relied upon by the UN, the World Bank, and other agencies – have been wildly overstated. A team led by Nancy Harris of the respected research firm Winrock International confirms that claims of alarming levels of carbon emissions from deforestation in tropical regions have been unfounded.

These previous erroneous claims have been used to advance harmful policies designed to limit agriculture and land conversion in Malaysia and elsewhere.

Those of us close to the economic, social, and agricultural realities on the ground are not surprised by the new emissions findings. We have long suspected they were seriously deficient and significantly wide of the mark.

For starters, the cultivation of palm oil sequesters more greenhouse gas than it emits. While this fact may be an inconvenient truth to environmental NGOs, it nonetheless helps explain some of the new and more precise emissions numbers.

And while environmental NGOs and European government officials may not yet realise it, the cultivation of palm oil can even save land from deforestation.

As a high-yielding crop, oil palm can generate enough income to help satisfy the economic needs of farmers, plantation owners, and governments. Sufficient revenues mean more forests can remain undisturbed or become rehabilitated.

Sabah, for example, has seen sales tax income from the oil palm industry bring greater revenue than the export tax collected from timber. As a result it has been able to reduce logging and allow its forest to regenerate. In this way, Sabah has half its land area conserved as forest while using less than 15% of its area for agriculture.

The assembled delegates also expressed emphatic support for maintaining and extending an open economic trading system. This means Malaysia and other aspiring economies will continue to compete on the global stage, harnessing our natural talents and endowments to power our economic rise.

It was 20 years ago that the first global ecological summit was held in Rio. And over the past 20 years, many green organisations and their friends in governments in rich nations have pursued ideological agendas at the expense of developing world realities.

But reality and the tide of history can only be held in check for so long. The news out of the Rio+20 summit is that our voices are finally being heard, respected, and heeded. While there is still much work to do to defend our interests and bolster our economic development, a major victory was realised this June.

Tan Sri Dr Yusof Basiron is CEO of the Malaysian Palm Oil Council. For more information or comments, e-mail yusof@mpoc.org.my.

Finally, good sense prevails over the airheads!

Palm is native to the wetlands of western Africa, and south Benin already hosts many palm plantations. Its ‘Agricultural Revival Programme’ has identified many thousands of hectares of land as suitable for new oil palm export plantations. In spite of the economic benefits, Non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as Nature Tropicale, claim biofuels will compete with domestic food production in some existing prime agricultural sites. Other areas comprise peat land , whose drainage would have a deleterious environmental impact. They are also concerned genetically modified plants will be introduced into the region, jeopardizing the current premium paid for their non-GM crops.